What Makes a Property Suitable for Social Housing Tenants?

Discover what makes a property suitable for social housing tenants and how standards differ from traditional buy-to-let.

SOCIAL HOUSING

Seven Generations Property Brokers

9/29/20259 min read

Social housing investing is often promoted as a hands-off, predictable alternative to the ups and downs of traditional buy-to-let. For landlords used to ASTs, the attraction is obvious: contracted rents, long-term leases and the reassurance of professional management. But one point that’s often overlooked is that not every property will make the cut.

Providers like Serco, Mears and Nacro operate under strict government contracts. When they lease a property, they’re responsible for housing vulnerable service users, from asylum seekers to people with disabilities or women fleeing domestic violence. Because of that responsibility, their property standards are far more rigorous than those applied in the open rental market. A house that could be marketed tomorrow on Rightmove under a normal AST might fail a social housing inspection at the very first hurdle.

We look at what makes a property suitable for social housing in the UK, along with how those requirements differ from AST lettings and why you need to understand them before pursuing this attractive type of buy-to-let.

Contents

Get in touch with one of the team to discuss what properties we have available for sale.

Interested in Social Housing HMOs?

1. ASTs vs Social Housing: Different expectations from the start

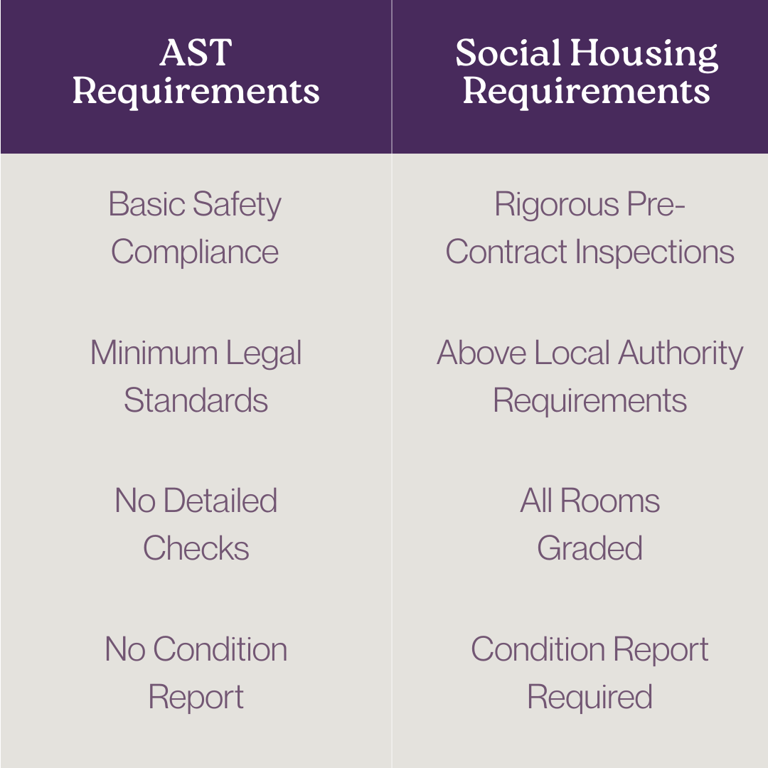

An assured shorthold tenancy (AST) is the standard private rental agreement in England and Wales. It sets out the rent, deposit and notice terms, but it rarely dictates anything about the physical structure of the property beyond basic safety compliance.

A landlord renting under an AST has to provide a safe, habitable home that meets minimum legal standards, such as working smoke alarms, a gas safety certificate and an EPC rating of E or above (although this is subject to ongoing consultation and possible legislative adjustment).

Beyond that, it’s up to the landlord. The kitchen can be ten years old. The carpets may be worn. A leaky tap might not breach any rules. If the property is liveable and legally compliant, it can be let.

What about Social Housing?

Social housing leases are different. Providers inspect properties against a long checklist before they’ll pass the property. Every room, fixture and appliance is scrutinised. The property is graded against standards that often go well beyond local authority requirements, and a condition report is drawn up before the lease is finalised.

Social housing has proven to be an attractive source of investment, with net yields of 9% to 10%, which are typically 2.5 to 3 times higher than standard buy-to-let investments, where net yields often fall in the 3% to 4% range. But it does mean landlords looking to invest in social housing need to be prepared for a much higher bar.

2. Compliance and Certification

A traditional buy-to-let property will need to meet clear safety and energy standards before it can be let. Checks are there to protect tenants and provide landlords with proof that the home is fit to live in. Generally speaking, you need:

an annual Gas Safe certificate

an Electrical Installation Condition Report (every five years)

an EPC showing a rating of at least E

a smoke alarm on each floor and a carbon monoxide detector near solid fuel appliances

That’s the legal minimum. Many landlords do the bare essentials, and letting agents don’t ask for much more.

By contrast, a social housing provider will demand a full suite of certifications, many with longer validity periods remaining at the point of onboarding. These can include:

Gas Safe certificate with at least nine months remaining

EICR with at least two years remaining

Fire alarm and emergency lighting certificates (minimum six months remaining)

Fire risk assessment with evidence of fault resolution

Asbestos survey and management plan

Legionella risk assessment

Building control sign-offs for any works

PAT tests for appliances

Energy Performance Certificate

The difference is pretty stark. A landlord letting under an AST might only think about gas checks once a year and book an electrician once a decade. A landlord preparing a property for social housing should have a complete compliance file ready to hand over, and keep it updated.

3. Fire Safety: From minimum legal standard to rigorous inspection

Under an AST, fire safety typically means fitting smoke alarms and making sure exits aren’t blocked. There’s unlikely to be a legal requirement for fire doors in most single-family lets, and certainly no expectation of an integrated alarm system.

Social housing providers, however, insist on HMO-level standards even when the property isn’t a student house or a typical shared rental. Every risk room and circulation space must have interlinked smoke and heat detectors, while bedroom and kitchen doors are replaced with fire-rated doors fitted with intumescent strips, smoke seals and self-closing mechanisms.

Escape routes have to be clearly signed, sometimes supported by emergency lighting if the layout is complex. Even the kitchen fit-out reflects this heightened focus on safety, with fire blankets a compulsory addition alongside the usual appliances.

For many standard buy-to-lets, these upgrades require significant investment. Bedroom doors in a three-bed terrace, for example, would need to be replaced with FD30s fire doors, fitted with compliant locks and closers. In an AST, the same property could legally be rented without any of these changes.

4. Kitchens, bathrooms and everyday fixtures

The contrast is just as clear in the day-to-day facilities. A property rented under an AST only needs to provide basic kitchen and bathroom facilities. There’s no set rule for socket placement or obligation to provide specific furnishings. You don’t have requirements for brand-new floor coverings.

In social housing, the standards are spelled out in detail. For example:

Even furnishing standards apply. If the property is accepted as furnished, everything from mattresses to wardrobes need to be new and compliant with fire regulations. It’s a level of detail that reflects the reality of service users often being vulnerable. The property must be robust and hygienic. In other words, it needs to be safe in ways that go beyond ordinary lettings.

5. Structural Integrity and Environmental Factors

Local authorities set out minimum HMO space standards and rules around overcrowding, but private landlords on ASTs can often sidestep these by letting to families rather than multiple households.

Social housing providers won’t. They’ll inspect the structure in detail, which means:

Roofs must be watertight, chimneys secure and roof voids free of debris

Ceilings and walls must be free from holes and fire-stopped where services pass through

Damp and mould must be eradicated entirely before onboarding

Windows must be double-glazed, lockable and fitted with restrictors where needed

Ventilation must meet strict standards, including extractor fans in kitchens and bathrooms

Heating must be modern, efficient and safe. That means no back boilers or decorative gas fires allowed

An AST landlord might shrug off condensation as the tenant’s responsibility (though, in an ideal world, they shouldn’t). A social housing provider will not. They expect the building fabric to be sound and any risk to health to be addressed before tenants move in.

Get in touch with one of the team to discuss what properties we have available for sale.

Interested in Social Housing HMOs?

6. External Areas & Security

When a landlord rents under an AST, expectations for the outside space are fairly limited. The garden should be reasonably tidy, and the fencing needs to be secure. Then there’s the bins, which must be the right type and in place. Outside of those basics, presentation tends to be a matter of preference rather than compliance.

Social housing leases work differently and providers carry out detailed checks of everything from paving and pathways to the condition of steps, making sure there are no trip hazards.

Boundaries such as fences and hedges are assessed not only for appearance but also for the level of security they provide. Entry points receive closer attention too, with external doors required to be fitted with thumb-turn locks that can be used without a key, while windows in lower parts of the property may need safety glazing.

Gardens are judged on more than simple tidiness; weeds, access routes and general upkeep all form part of the inspection. Outbuildings and sheds are either secured or taken down if they don’t meet standards, and providers also look at finer details.

Details that might seem minor in an AST let, such as how clearly the property is numbered or whether the exterior is well lit, become part of the inspection for a social housing lease. Providers also check that meter cupboards are secure and in good working order. If any of these points are missed, the lease won’t be signed until the landlord has made the improvements.

7. Inspections and Condition Reports

The biggest procedural difference between ASTs and social housing leases is the inspection process. With an AST, a letting agent might spend half an hour walking through the property and take some photos before drafting up a marketing description. Once a tenant moves in, periodic inspections can be little more than a box-ticking exercise.

Social housing providers take a different approach and send trained inspectors to evaluate the property against a comprehensive checklist, often running to more than twenty pages. Every defect is logged, from loose hinges to worn grout. The outcome is a condition report, which sets out the schedule of works required before the lease can begin.

For landlords, this can feel demanding, but it also provides clarity. Once the property meets the standard, it’s signed off, and the lease is activated. The difference compared to ASTs is that there’s no ambiguity – either the property is suitable, or it isn’t.

8. Local Authority Involvement

With an AST, local authority involvement is limited to licensing in certain areas (for example, HMO licensing or selective licensing schemes). For single-family lets, councils rarely intervene.

In social housing, local authorities are much more involved. Even when a provider like Serco signs a lease, the property still has to meet local authority requirements around HMO licensing, planning (including Article 4 restrictions) and amenity standards.

That creates a double compliance layer: landlords have to satisfy both the provider’s standards and the council’s rules. In practice, the provider often sets the higher bar, but councils can still block or delay leases if their conditions aren’t met.

9. Why Not All Properties Qualify

A combination of strict provider standards, local authority rules and detailed inspections explains why not all properties are suitable for social housing investment.

A flat in a converted block with high service charges may never pass the cost-benefit test for a provider. A house with an old boiler or poor insulation will need upgrades before approval. An HMO in an Article 4 area may be off-limits altogether without planning consent.

By contrast, a landlord renting under an AST could let those same properties tomorrow, provided they meet minimum safety laws. That’s the key difference. The open market sets a low bar, but social housing providers set a high one, and they enforce it rigorously.

10. What It Means for Social Housing Investors

For investors, the implications are clear. Social housing can deliver contracted rents and strong net yields, but only if the property passes inspection. That means:

Understanding provider standards before purchasing

Factoring in the cost of upgrades and compliance work

Working with brokers and developers who know how to prepare stock for inspection

Accepting that not every property on the open market is a candidate

It also means recognising the trade-off. While AST lets may offer more flexibility – you can sell or remortgage more easily, and you can pick from a wider range of stock – social housing leases demand more upfront preparation but reward it with stability.

11. How Seven Generations Can Help

Social housing investing is a contract-driven model that requires properties to meet stringent standards before vulnerable tenants are housed. It’s not just another form of buy-to-let, and compared to ASTs, the expectations are higher at every stage. It’s about the fit-out quality and you need to consider external presentation and ongoing inspections.

Not all properties will qualify, and landlords should be prepared for detailed scrutiny. However, if you meet the standard, the reward is a lease that takes the headaches out of buy-to-let with guaranteed rent, professional management, and the reassurance that the property is not only profitable but also safe, compliant, and serving a real social need.

We sell compliant social housing investments, connecting you with providers offering long-term leases and contracted rents. Start your social housing investment journey

Get in touch with one of the team to discuss what properties we have available for sale.

Interested in Social Housing HMOs?

Registered Company Number: 15439671

Copyright © 2025 Seven Generations UK Limited, All Rights Reserved

PRS Membership Number: PRS043981

Your trusted partner for UK buy-to-let property

Quick Links

Contact Us

ICO Membership Number: ZB694046

Properties For Sale